When the Civil War ended in 1865, major questions emerged about who, exactly, was entitled to the right to vote. Throughout the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877), a number of suffrage movements organized to promote voting rights for women and African Americans. Women’s rights leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Virginia Minor argued that women held the right of citizenship and, by extension, the right to vote. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass argued that African American men who had fought in United States Colored Troops Regiments during the Civil War had earned the right to vote.

Congress held numerous debates about creating some sort of constitutional amendment to achieve these ends. For moderate and radical Republicans, black suffrage was both morally right and a chance to expand their political base in the South. Civil War General and Congressman James A. Garfield argued in 1865 that “each man has a right to be heard on all matters relating to himself . . . Let us not commit ourselves to the absurd and senseless dogma that the color of the skin shall be the basis of suffrage. Let suffrage be extended to all men of proper age, regardless of color.” Numerous Northern states including Connecticut, Minnesota, and Wisconsin put black suffrage up for a popular vote during the early years of Reconstruction. There was much resistance to both women’s and African American voting rights, however. Every ballot initiative on suffrage rights in the North failed to pass (women would not get the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920). Democratic Congressman James Brooks of New York reflected this opposition when he stated that “From the great history of the world the negro has not the capacity of self-government. Wherever the superior race has shared government with him destruction has been the lot of both.”

Ulysses S. Grant evolved in his views and gradually came to support black voting rights. He acknowledged in his Personal Memoirs that he initially supported the idea that African Americans would first experience “a time of probation, in which the ex-slaves could prepare themselves for the privileges of citizenship before the full right would be conferred.” The actions of President Andrew Johnson worried Grant, however. Grant believed that Johnson’s lenient amnesty policies towards former Confederates had emboldened them, leading to possible future conflict between the sections. “The Southerners had the most power in the executive branch, Mr. Johnson having gone to their side,” Grant argued. By 1868 it became clear to Grant that African Americans were the most loyal Southerners to the Union and in need of additional protection. By vesting black men with voting rights, it provided stability to the country moving forward. “While strongly favoring the course that would be the least humiliating the people who had been in rebellion, I had gradually worked up to the point where, with the majority of the people, I favored immediate enfranchisement [for African Americans],” Grant argued.

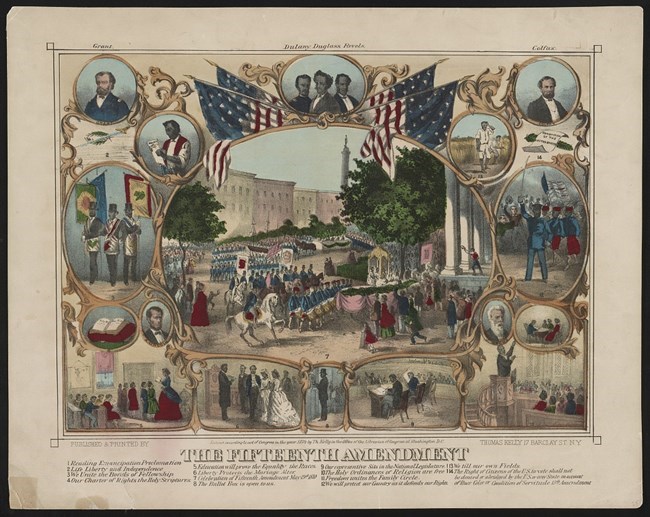

The 15th Amendment was ratified on February 3, 1870. It states that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Below is a special message President Grant wrote to Congress on March 30, 1870 explaining his perspective on the meaning of the 15th Amendment for the future of the United States.

Special Message

March 30, 1870

To the Senate and House of Representatives:

It is unusual to notify the two Houses of Congress by message of the promulgation, by proclamation of the Secretary of State, of the ratification of a constitutional amendment. In view, however, of the vast importance of the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution, this day declared a part of that revered instrument, I deem a departure from the usual custom justifiable. A measure which makes at once 4,000,000 people voters who were heretofore declared by the highest tribunal in the land not citizens of the United States, nor eligible to become so (with the assertion that "at the time of the Declaration of Independence the opinion was fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race, regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, that black men had no rights which the white man was bound to respect"), is indeed a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free Government to the present day.

Institutions like ours, in which all power is derived directly from the people, must depend mainly upon their intelligence, patriotism, and industry. I call the attention, therefore, of the newly enfranchised race to the importance of their striving in every honorable manner to make themselves worthy of their new privilege. To the race more favored heretofore by our laws I would say, Withhold no legal privilege of advancement to the new citizen. The framers of our Constitution firmly believed that a republican government could not endure without intelligence and education generally diffused among the people. The Father of his Country, in his Farewell Address, uses this language.

Promote, then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

In his first annual message to Congress the same views are forcibly presented, and are again urged in his eighth message.

I repeat that the adoption of the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution completes the greatest civil change and constitutes the most important event that has occurred since the nation came into life. The change will be beneficial in proportion to the heed that is given to the urgent recommendations of Washington. If these recommendations were important then, with a population of but a few millions, how much more important now, with a population of 40,000,000, and increasing in a rapid ratio. I would therefore call upon Congress to take all the means within their constitutional powers to promote and encourage popular education throughout the country, and upon the people everywhere to see to it that all who possess and exercise political rights shall have the opportunity to acquire the knowledge which will make their share in the Government a blessing and not a danger. By such means only can the benefits contemplated by this amendment to the Constitution be secured.

HAMILTON FISH, SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE UNITED STATES.

To all to whom these presents may come, greeting:

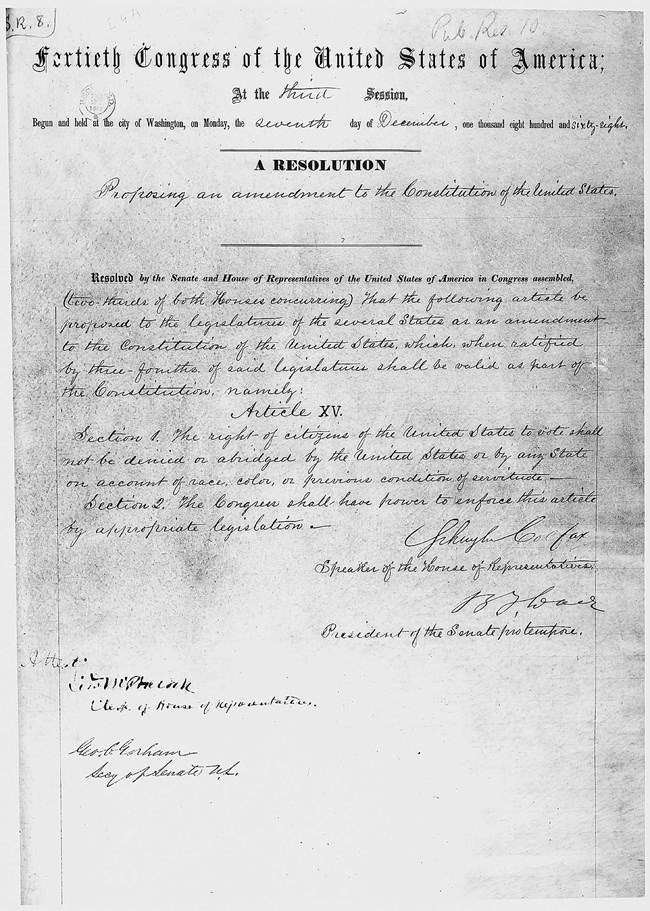

Know ye that the Congress of the United States, on or about the 27th day of February, in the year 1869, passed a resolution in the words and figures following, to wit:

A Resolution proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled (two-thirds of both Houses concurring), That the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several States as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said legislatures, shall be valid as a part of the Constitution, viz.

SECTION 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

SEC. 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

And further, that it appears from official documents on file in this Department that the amendment to the Constitution of the United States, proposed as aforesaid, has been ratified by the legislatures of the States of North Carolina, West Virginia, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Maine, Louisiana, Michigan, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, New York, New Hampshire, Nevada, Vermont, Virginia, Alabama, Missouri, Mississippi, Ohio, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Rhode Island, Nebraska, and Texas; in all, twenty-nine States;

And further, that the States whose legislatures have so ratified the said proposed amendment constitute three-fourths of the whole number of States in the United States;

And further, that it appears from an official document on file in this Department that the legislature of the State of New York has since passed resolutions claiming to withdraw the said ratification of the said amendment, which had been made by the legislature of that State, and of which official notice had been filed in this Department;

And further, that it appears from an official document on file in this Department that the legislature of Georgia has by resolution ratified the said proposed amendment:

Now, therefore, be it known that I, Hamilton Fish, Secretary of State of the United States, by virtue and in pursuance of the second section of the act of Congress approved the 20th day of April, in the year 1818, entitled "An act to provide for the publication of the laws of the United States, and for other purposes," do hereby certify that the amendment aforesaid has become valid to all intents and purposes as part of the Constitution of the United States.

In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the Department of State to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington this 30th day of March, A. D. 1870, and of the Independence of the United States the ninety-fourth.